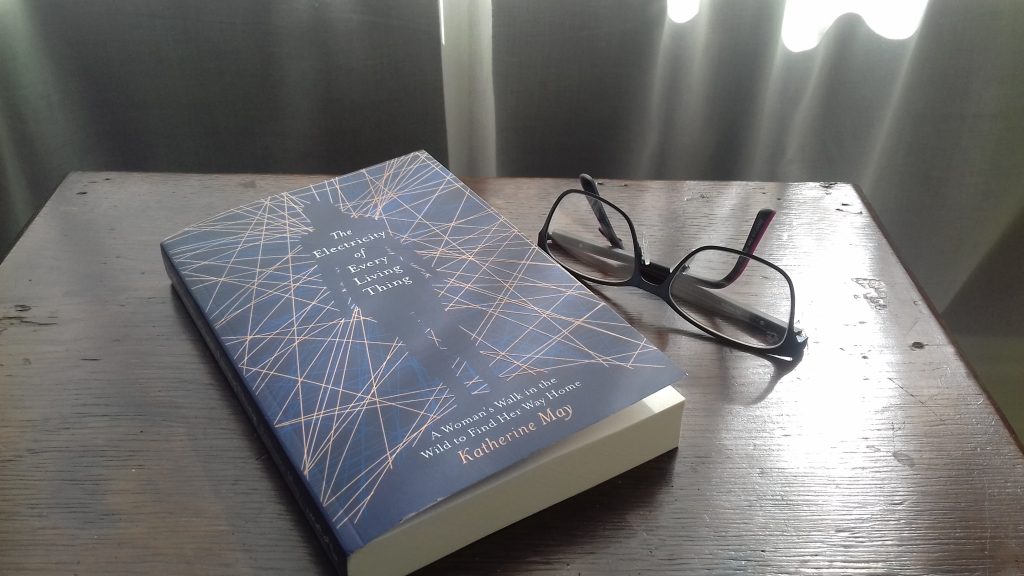

The Electricity of Every Living Thing: a woman’s walk in the wild to find her way home by Katherine May. Published by Trapeze, 2018. Out in paperback May, 2019.

This is a book filled with gold. Beyond the glittery lines that dart across the cover, golden threads are echoed within the text. The illustration on the front of this newly published paperback edition represents the electric charges the author feels in everything that surrounds her – her body a conductor to them all. The gold in the text is the sharp and direct writing that illustrates in fine and very human detail, the breadth and depth to which autism has impacted on the author’s life. The Electricity of Every Living Thing shines light into the inner most world of a woman who has grown up and travelled through life being dismissed and disparaged by teachers and doctors alike, while adapting to and tolerating a world that painfully jars at every turn.

Believing she just couldn’t cope as well as other people, May developed a careful and thoughtful system of navigating her world, copying those she thought dealt with things better than she did. This worked really well in many ways – right up until the points when it didn’t. For May, this latest point was having her son Bert, and all that brought. The unpredictability and high demands of a new baby and the physical changes that impacted on her body, and May was again feeling that she just couldn’t cope. It left her confused about why it seemed so much harder for her than it was for other mothers. It was different. But with a lifetime of asking for and being denied help, she was reluctant to pursue this path again. It laid the foundations for something else, something that began to stir while listening to a radio programme in the car one day. It was more than stirred when the insensitive interviewer asked about how challenging romantic relationships could be for autistic people. She was silent no longer:

“How fucking dare you? We’re not completely repellent, you know…”

And in that moment, May heard herself say that one small word: ‘we’. Aside the ineptness of the host, she had heard enough to sow the seed in those rich foundations of seeking answers and understanding to begin to want to know more. She had begun to recognise something of herself. But what a blow – it’s a lot to take in and to take on, a diagnosis. Even more, it’s a lifetime of beliefs, of stereotypes and misunderstandings, all of which need to be undone before a new sense can be made. And this book documents that, offering a new script to her story – one she has claimed for herself – and with it, a window for others to see into, to understand better. It charts the progression of her walking through seascapes and countryside as she reconsiders her sense of self. It is a skilfully written description of the world as May experiences it. A treasure trove of insights into what it can be like for an autistic person. It is also much more than a book about a woman who learns she’s autistic.

With an initial plan to walk the South West Coast Path in its entirety from north to south, May set out alone. Woefully unprepared for the physical demands and geographical challenges, she had a need to be outside, to be by the sea, and to walk. Living in Kent, this meant regular weekends away and a series of family trips to the west coast. Living in Kent, and having always lived in Kent, the author begins to explore her home turf on foot too, and begins to walk the North Downs Way – in part with an increasing need to walk and in part a re-orientation of herself, finding her path and finding her place.

“…to know the full extent of my world; to trace its boundaries with my feet; to take the longest, hardest way round.”

May is drawn to the coast. She writes of the importance of this to her and creates the atmosphere of the south east and west as she writes and walks. There is a kind of mirroring in the book – a rhythm of looking outwards and inwards that is reflected in the worlds between Kent, Devon and Cornwall. One place shows up things about the other, each giving her a different kind of space. She learns more about her own home county that she had never thought to question before, the familiarity of place we learn to accept when we’ve always lived there. Going away shifts this, the dislocation felt at home is shown in her early walks in Devon as she gets to grips with the coastline and the weather, and the physical demands of each.

The Electricity of Every Living Thing gives an account of challenges experienced as an autistic person. It also gives a very frank account of challenges as a woman, a mother, and more generally so, what it is like to be human. May has the sensitivity and skill to be able to see these things and write about them in ways that make the reader see them anew, without airbrushing flaws and vulnerabilities.

The freshness of the writing matches the honesty of May’s descriptions of her internal world. In search of some peace, she is confronted not only with the harshness of the natural world and it’s weather but also with her own thoughts and memories. Spending time in the outdoors, alone, with so much space for reflection it seems inevitable, that she is confronted with herself. The empty space craved, to replenish and recuperate – an escape from the busy and hectic, from the day to day mundane – and it is us we are left with, curses! She had not escaped, as intended, but thrown herself headlong towards herself – into the most unforgiving of places to navigate difficulty.

In the early chapters May writes of the endless times she cursed herself, cursed the weather, and cursed the world for the path being so bloody hard – for life being so bloody hard – and for her not to have known, to have prepared better, to be better at coping with it all. Her husband, H, and 3 year old son, Bert, make regular appearances as her (usually) reliable back up crew and support system, in joyous and infuriating ways.

Navigating a tricky path, not just of the jagged rocks and sheer drops of the coastline, but also of her own vulnerability and resilience, May shows a sharp wit, articulate voice and awesome ability to swear loudly. Her self doubt and pain is powerfully shown when seeing herself through the eyes of others – hearing herself described as ‘intense’ and ‘Marmitey’. I think of the fragility of the coastline and all it withstands, it is a pertinent parallel.

The South West Coast Path is undoubtedly a tough walk to take, and perhaps this is the reason that May chose it, and why it becomes such a hard space to be alone in. If you can be at peace in such a brutal and exposed place, perhaps then it is possible to be at peace anywhere.

Katherine May shows us how fallible she is, how unprepared she is and what she discovers as she does it anyway. This is a testament for us all, none of us really know what we are doing up until that point of learning and discovery. There is no preparation for life, for motherhood, for finding out you are different. These are some of our greatest challenges as human beings. There is probably some preparation that can be made in setting out on the South West Coast Path, but it’s essentially through the doing that learning happens. And we learn and develop and adjust to our environment. May had spent many years of her life attuning her social skills, adjusting to the world around her – often to her own detriment. It was now time for her to stop and to see what would happen.

Drawing on the understanding of place from other parts of the world, she lands on an understanding of territory from Aboriginal culture. This weaves ancestry, landmarks and walking routes. May is tracing and singing her own songlines. She is rewriting and reframing her experiences and taking up the space she needs in which to do it. After learning to be away she begins to learn to be able to stay. Things get rearranged, everything finds its fit and a new place is made.

The reconnection to place made back in Kent, is also done through walking, through finding the new in the familiar. Referencing other writers throughout the book, May brings a wider sense of place – the cliff tops and sea birds, rock pools and beaches sit alongside the people who have inhabited these spaces, and those she meets and spends time with along the way. Through this to and fro of place and space – from internal to external, and west to east – May finds that her feelings become clearer, that her sense of herself and her place in the world settles. An attempt to find a name for this thing that has always made life so hard, the word ‘autistic’ gives her a clarity, and perhaps a kind of permission to be all the things she has always been. It’s an explanation. This new word helps to understand. She has by now become pretty adept at dealing with it, but a name gives her a place to put these things – to find a place for them and for that to be ok.

Overcoming her years of being dismissed and discredited as a witness to her own experience, May learned that, not only is she dealing with much more than someone who is not autistic (neurotypical), but that there are aspects of her experience that are shared by many, and there is support and strength in the discovery of this new community. As might be expected, in a walk of this kind, she does indeed come to an acknowledgement, an acceptance, and ultimately a celebration of the things autism brings her, as well as acknowledgement of the challenges it creates.

Within the humour, cursing and the beautiful writing, there is a very painful story told. A story of May growing up and finding life difficult and distressing, of asking for help and being dismissed, not just once but time and again. I am cut to the quick to read of appointments with GPs, counsellors and psychiatrists, regularly disregarding her concerns as anything ‘substantial’. These are not just contacts that have left her feeling that there is nothing that much to be concerned with, but professionals tasked with a duty of care who have actually told her this – professionals, utterly unaware of their own failings, their own lack of understanding and ability. Her last encounter with a sympathetic GP, one who has known her for years and is as surprised and thoughtful about her wonderings about autism as she is, is a joyous conclusion. This book will I hope be read by many practitioners, to become as much a part of their reading list as any text book. I hope it helps to bridge the gap between patient and doctor in the consulting room, while it will continue to chip away at the unhelpful and damaging stigmatising of difference in the wider world. This is something May has had to overcome – an additional burden to anyone receiving a diagnosis, the stigma a wholly unnecessary extra.

The Electricity of Every Living Thing is a story of a life well told and it is a story that will connect with many people, of autism yes, but also of the treatment by health care professionals when they don’t know the answers, of motherhood and of reaching a time in your life when you begin to reflect and question things more deeply. To do this in the setting of wild landscapes that are relentless and without mercy is a challenging path to take. Beyond all of these threads that weave throughout the book, this is a brilliant tale about walking and being in the outdoors.

“Everybody has a song like this. A song that is a map, a compass: a song that sets you straight again. Learn it, and it will take you home.”

For anyone reading The Electricity of Every Living Thing and with more questions about autism, Katherine has put together a number of resources here: www.electricityofeverylivingthing.com/resources

Katherine May is an author of fiction and memoir, and an award-winning blogger. She has also published The Whitstable High Tide Swimming Club, The 52 Seductions (as Betty Herbert), Burning Out, and Ghosts & Their Uses. Until recently, Katherine was the Programme Director for the Creative Writing MA at Canterbury Christ Church University. She currently works as a literary scout for Lucy Abrahams Literary Scouting and reads for Faber Academy.